With a running time of more than eight hours, Andy Warhol’s Empire is generally acknowledged to be the most boring film released in 1965. Four years later, a German artist named Hanne Darboven succeeded in producing a movie that was even more monotonous.

Six Books on 1968 was shorter than Empire. But unlike Warhol’s movie – comprising a stationary view of the Empire State Building from 8:06 PM to 2:42 AM, screened in slow motion at sixteen frames per second – Darboven’s film had no subject matter. Or to be more precise, her subject was time itself. Darboven filmed a calendar.

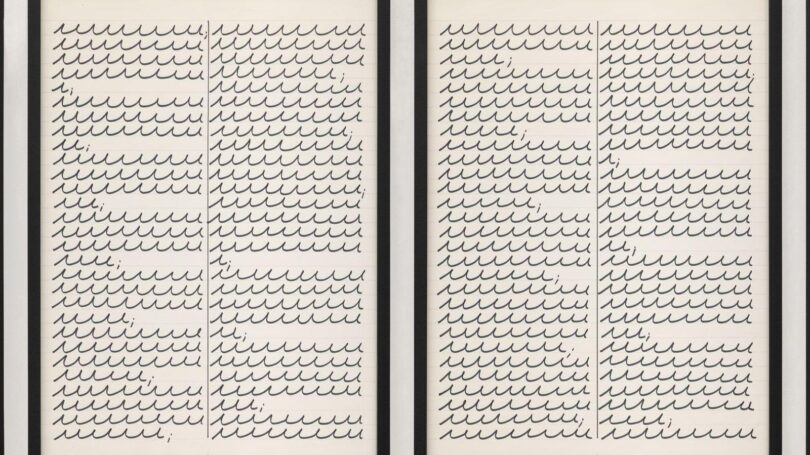

Detail view of Hanne Darboven’s Untitled (ohne Titel), ca. 1971–73. Felt-tip pen on 4 sheets of … [+]

Monotony was already a favorite subject for Darboven, as can be seen in a new retrospective at the Menil Collection, a show without a hint of showiness that is paradoxically enthralling. Her earliest mature work, produced in 1966, was created on graph paper with a pencil and ruler, charting mathematical functions she calculated by hand. She provided no explanation for these laborious “constructions”, only occasional cryptic notation marking certain geometric configurations as “restless” or “quiet”. Their hold on the viewer derives from their mysteriousness, from Darboven’s seriousness, from her evident need to work something out as if the world depended on it.

Darboven’s hand-drawn calendars are simultaneously clearer and more enigmatic. They derive from a mathematical system of her own invention, requiring that dates be tallied by adding up the day, month, and last two digits of the year. This calculation, which she called the K-value, had the effect of scrambling everyday chronology. (For instance, January 23, 1968 had the same K-value as March 21st.) This disorientation is further enhanced by displaying K-values as rows of empty boxes on sheets of graph paper and binding the sheets in numerical order.

Six Books on 1968 shows each page of the six books she made on six reels of film screened simultaneously on six side-by-side projectors. The effect is to express the indication of time in terms of duration. The projection cannot be rushed. Both the time that she captured and the time that she took to capture it on paper are temporally decompressed and conceptually entangled. Warhol asserted that the purpose of Empire was “to see time go by”. Darboven admired the multiple levels at which Warhol’s films could be experienced, but her own movie was even more audacious. She set out to collapse representation and reality.

Hanne Darboven, Zeichnung [Drawing], 1968. Ink on paper, 40 1/2 × 28 3/4 × 1 7/8 in. (102.9 × 73 × … [+]

And she was just getting started. Enlisting monotony, Darboven developed a script to score K-values in their entirety, eschewing mathematical shortcuts such as decimal notation. This time-consuming demarcation of time provided the artist with “a way of writing without describing”.

As simple as it looked, Darboven’s system provided a solution to a problem that had confounded philosophers since antiquity. “What is time?” St. Augustine famously wrote in The Confessions. “If no one ask of me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not.” Darboven avoided the trouble of explanation by letting time answer for itself.

Darboven’s approach to time was also her approach to life. She was wary of all explanation and description. She sought to make language as real as anything it might reference. Transcribing whole books with no intention of reading them or allowing them to be read, she reduced words to ink on paper.

Holding language accountable in this manner, preventing words from expressing ideas in absentia, was ultimately a political act. “I would say that after the disquiet of death, war, and fascism, silence is the highest matter of interest that one can practice,” Darboven proclaimed in a 1991 interview. Time-consuming monotony provided a way to enact silence – an enactment that can still be experienced through Darboven’s extraordinary work.