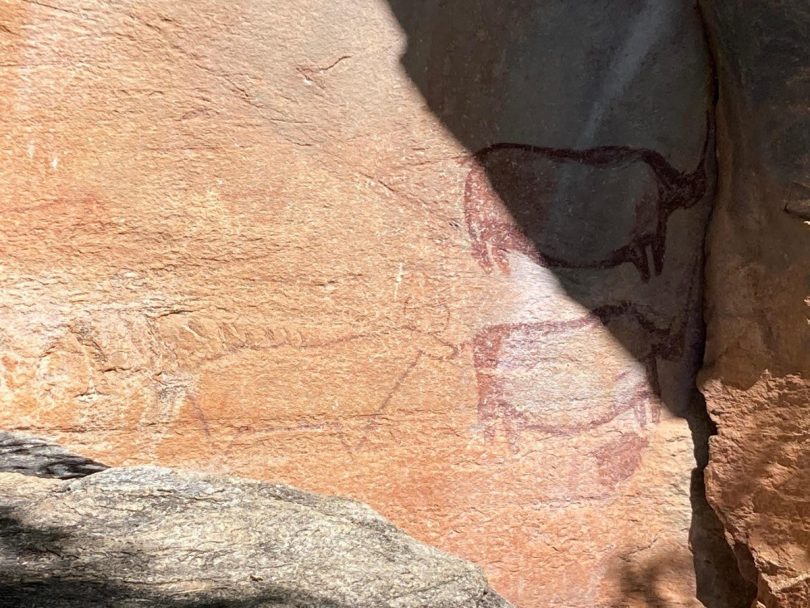

Tsodilo Hills pictographs.

The Louvre of the Desert.

Tsodilo Hills in Botswana has often been referred to in the West by this catchy slogan. As is often the case with Eurocentric perspectives adhered to Indigenous cultures around the world, the metaphor misses the point entirely in its attempt to characterize what makes this place special.

Tsodilo Hills exists today as it did for the ancient inhabitants who created the pictographs there as a sacred place.

It is not a museum. It is not a storehouse for pictures.

Categorizing Tsodilo Hills as such is dismissive if not insulting; an example of the ongoing colonial legacy of reducing Indigenous practices to notions conforming with Western standards.

The shamans who hand-painted some 4500 images onto the rock faces at Tsodilo Hills were not compelled to do so by man’s innate need to create. They were not attempting to solve pictorial problems of form or perspective like artists. They weren’t artists at all.

The shamans at Tsodilo Hills were painting visions received from their gods, not artworks.

Africa. Botswana. Tsodilo hills. (Photo by: White Fox/AGF/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Observed are the animals, people and shapes which were revealed to them while in trance. The ochre handprints on the cliffs are not signatures or decoration, they are the physical, historic manifestations of how the shamans connected with the spiritual through these rocks.

The paintings share stories.

The camouflaged hunter who killed an eland. The arrow he shot it with. The hide he preserved. The celebration which followed.

The paintings share history.

These are markers from the people who lived here, documenting how they lived–that they lived–that they lived in this place, and this is what they saw.

“We were here. These animals were here with us,” they seem to say.

There are more paintings of animals than people, evidence of how essential animals were to their way of life. The humans wouldn’t have existed–not here–without them.

Marginalizing Tsodilo Hills by associating its primary value through the prism of art diminishes the impact of both the Hills and the drawings. Doing so is akin to admiring the Hagia Sofia foremost for its mosaic tiles or the Vatican for its stained glass.

“This is the mountain of the gods. It’s still the mountain of the gods,” Tsodilo Hills guide Lopang Majanga (Hambukushu) told Forbes.com.

From the ancient to today

Tsodilo Hills pictographs.

Remnants of these ancient visions, in situ–remarkably well preserved–affords conscious visitors a rare opportunity to plug in to the spirituality which inspired them. The spirituality these hills maintain.

All tours of Tsodilo Hills are led by residents from the tiny nearby village of Tsodilo; each guide has been approved by a community trust to interpret the site for guests.

“I am from this place. I love this place. I want to show people,” Majanga said. “I like it when people take an interest in this place.”

As a “history teller” himself, with an Indigenous understanding of the Hills given him by his parents and elders, Majanga doesn’t simply pass along the knowledge left behind by the painters–his ancestors–in a very real way, he’s following in their footprints. Majanga and his fellow guides are torchbearers for the ancients, the modern-day storytellers of Tsodilo Hills.

“I give a lot of respect to them and the respect that I give to them is the respect that connects me with them,” Majanga said of the shamans who painted Tsodilo. “They are so special to me because they were my great grandfathers.”

Recognizing the direct descendant relationship between the ancient painters and the present-day guides proves critical to appreciating the Hills’ significance.

“I believe in ancestors,” is Majanga’s simple reply when asked about the Hills’ continuing spiritual importance, adding, “It’s a very sacred place to be. Sometimes I just go by myself next to the Hills and listen. It’s something that heals my heart inside and it keeps me close.”

What to see at Tsodilo Hills

Tsodilo Hills white pictographs.

Tsodilo means “damp earth” in the !Kung language. While the Hills now reside in the Kalahari Desert, 10,000 years ago, a lake could be found here. The !Kung and Hambukushu are the area’s current residents. Both groups fall under the broader category of “San” people or “Bushmen” indigenous to the area.

Human habitation in the area dates back 100,000 years to the first anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens). Precise dating of the paintings proves impossible, but a general consensus puts the earliest of them at over 20,000 years.

These are the red paintings attributed to the Ncaekhoe according to signage at Tsodilo Hills. Through its millennia of habitation, numerous tribes frequently migrated through the area and lived here.

Pink haematite with a high iron content gives these paintings their dramatic color. The mineral was mixed with charcoal, calcrete, animal fat, blood, urine, marrow, sap and egg white to produce the paint which was applied by hand. This technique varies from other rock painting sites in Africa produced by brush.

More recent white paintings, lacking haematite, some dating from the 1800s, were completed by the Bantu.

The paintings have survived because their creators took care to intentionally place them on rock faces shielded from the elements. The remoteness of this place and its protection by local residents have also prevented their damage, a fate which has befallen most of the other rock paintings around Botswana and southern Africa. Tsodilo Hills possesses the finest remaining examples of the kind.

Giraffe, rhino, monkey, gemsbok and lions are among the many animal species depicted. So too are penguins and whales. Presumably.

Did the painters of these ocean-going animals travel from the landlocked Hills to see them with their own eyes? The Indigenous people here were travelers.

Or did travelers from other tribes visit Tsodilo Hills and share knowledge of the animals they were familiar with?

Perhaps these aren’t penguins and whales after all. Maybe the whale is a hippo?

Tsodilo Hills guides lack the arrogance to pretend to definitively know what everything painted here means. They encourage guests to interpret the paintings for themselves.

Tsodilo Hills pictographs possibly of penguin and whale.

“Tsodilo has surprises,” Majanga said. “People can learn about the rocks. They can learn about the history that was happening around here and even the sacredness of the place.”

The only aspect at Tsodilo Hills not open for interpretation is its sacredness.

“Everything here is sacred, even the paintings,” Majanga reminds. “For them to have existed this long, we cannot say it’s just the paintings they did–no–also there’s a word of mouth that was said to the spirits for these things to have stayed longer.”

And there are places here, such as the python watering hole, too sacred to be shared with outsiders.

Visiting Tsodilo Hills

Desert & Delta Nxamaseri Island Lodge aerial view.

Day visitors are welcome at Tsodilo Hills every day, year-round, from 7:30 AM to 4:30 PM; for campers, it’s 6:30 AM to 6:30 PM. Entrance fees for day visitors aged 15 and up is 50 Botswana Pula, about $4 U.S. Children aged 2 to 10 are P10 per visit and anyone under age 2 is free. For overnight camping, adults pay P130, children P70 and under 2-years-old stay free.

Payment must be made in cash. American dollars and Euros are accepted along with Pula.

Tsodilo Hills Rhino Trail is the most regularly traversed. While not wheelchair accessible, a mostly flat portion of less than a half-mile puts visitors in front of a large number of paintings. The full circuit of the trail continues through steep inclines up and down boulders. Water and sunscreen are suggested to bear the harsh sun. Additional trails over the site’s other hills could easily turn a visit here into an active, all-day adventure.

Cost for the Rhino Trail guided tour is P120; Lion, Cliff and Male Hill Summit tours are P175. Guides earn their incomes through tips.

The nearest permanent accommodation welcoming tourists is Desert & Delta Safaris’ Nxamaseri Island Lodge. A locally based company celebrating its 40th year of operating safaris exclusively in Botswana, Desert & Delta acquired Nxamaseri in fall of 2021 after recognizing a hole in the country’s tourism portfolio and seeing an opportunity to fill it.

Desert & Delta Nxamaseri Island Lodge guest reception patio.

For all of Botswana’s natural treasures–the largest concentration of elephants anywhere on earth, the spectacular Okavango Delta, nearly 600 bird species–safaris here lacked the diversity of experiences offered in other African nations. Especially conspicuous by its absence were experiences offering tourists the chance to connect with Indigenous culture.

Enter Tsodilo Hills.

Designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2001, it offers a rich spiritual and cultural experience begging to be explored.

Yet visitors have failed to thus far arrive in large numbers.

For all its sacred importance and history, Tsodilo Hills lack the wildlife most tourists visit Botswana in search of. On top of that, Tsodilo’s location in a remote corner of a remote country makes it difficult to access for even the most intrepid.

Enter Desert & Delta Safaris.

Previously operated by private owners as a fishing camp on the Okavango River, Desert & Delta Safaris sees in Tsodilo Hills just the sort of cultural tourism product the country is seeking and its acquisition of Nxamaseri puts tourists only 90 minutes by vehicle or 20 minutes by helicopter from the site. Excursions there are included when staying at the lodge.

“At Nxamaseri, the star of the show is the cultural experience of Tsodilo Hills and the ancient rock art that is a manifestation of our Botswanan Indigenous culture,” Desert & Delta Safaris Marketing Director James Wilson told Forbes.com. “We are stepping out and committing to that history and that culture and making a statement by investing in this region that the Indigenous culture of Botswana is just as important as its wildlife, and by uplifting the communities surrounding Tsodilo Hills, we are investing in both the community and the wildlife simultaneously.”

The company’s hope is that by offering safari goers a powerful cultural experience to pair with the country’s unsurpassed wildlife, not only will its product be distinguished throughout Botswana, but across the whole of Africa.

Beyond corporate self-interest, Desert & Delta aspires for Tsodilo’s local residents to reap a portion of the economic windfall safari has brought more popular sites within the country by opening up this overlooked corner of it.

“Now that we’re operating a lodge in this region known as the Okavango panhandle, in the far reaches of the country, we’re going to be working with the local community in the area a lot more, as we do in all the other regions where we have lodges. We’ve already had a number of meetings with the local community trust and elders,” Wilson said. “We’re building a really good relationship. Whenever a tourism company invests in a local community-run experience, it has an obligation to treat the local partners with incredible respect. This is their community. Their land. Their ancestral home. As a commercial partner in the region, we don’t want to barge in and change things. We want to progress and engage, work together slowly towards a common goal so we can showcase our commitment to the communities in which we live and work and then look at ways we can thoughtfully add value.”

That added value may come in the form of additional training for guides or facility improvements at Tsodilo Hills or in the village.

Leading the way in Desert & Delta’s outreach to the Tsodilo community toward reaching a shared vision for the site’s tourism future are “Kevin” Bame Bethia and Kehutsitswe “Action” Gabaikanye–both native Botswanans.

Desert & Delta has long prioritized hiring, training and promoting Indigenous people from entry level to the highest echelons of management. All of the Desert & Delta Safaris camps have local citizen managers. This effort has allowed the company to approach the people living around Tsodilo Hills authentically as collaborators, not as outsiders looking to exploit their spiritualty.

Majanga, just 25-years-old, but already a seasoned guide with six years of service under his belt, was one of the figures Desert & Delta consulted with before moving into the area. He continues providing council.

Rightly so.

“This place has been my family’s place,” Majanga said. “I like to carry on with how they were living here.”