As companies making meat from cells raise money, create prototypes and improve their technology, they are getting closer to having products to make available.

And that leaves a question hanging in the air: What can those products be called?

The USDA — which formally agreed in 2019 to jointly regulate products in the cell-based space with the FDA — put out a formal request for input in September. The department asked a battery of questions about how these products should be described on packaging labels, especially compared to animal derived products. Which terms work best for this type of product? Which terms would be misleading?

The comment period was open for two months. And in that time, 1,179 comments came in.

Eighty-seven of them came from companies, trade groups, policy groups and international entities. State agriculture departments, companies involved with cell-based meat, traditional meat producers and an array of groups connected to the food industry commented. A total of 157 individuals left comments anonymously. One U.S. senator made his opinion known.

And while the comments offered a wide variety of viewpoints on cell-based meat, one sentiment was nearly universally shared: These new products represent something new and different, and they deserve regulators’ attention and specific labeling.

Deepti Kulkarni, a partner at law firm Sidley Austin LLP who previously worked in the FDA’s general counsel office on agency oversight and regulatory pathways for new and emerging technology, said that the process of inviting public comments and using them to inform new regulations uses significant governmental resources. However, it signifies the importance of this new area. And the fact that questions about labeling drew more than 1,000 comments makes sense to her.

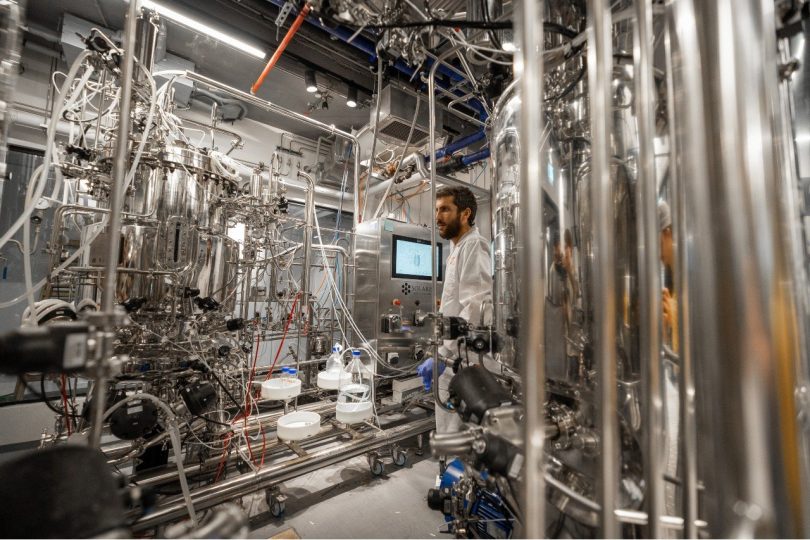

Future Meat Technologies’ pilot plant in Israel.

Courtesy of Future Meat Technologies

“That underscores the significant interest in these products and the technology,” she said. “That should not be surprising to anyone, right? What we feed ourselves and our families is a big part of our individual and cultural identity. And I think you see that in comments.

“Meat is a very big part of American culture, and so there’s a lot of people really interested and passionate about these issues,” Kulkarni continued. “At the same time, the world’s population is growing, and we understand more and more of the potential impacts of climate change. So a good number of people are reevaluating how and what they eat.“

Food Dive accessed, read and analyzed all of the comments that came in from companies, interest and industry groups, state and foreign government agencies and officials, and prominent individuals. All of these comments, complete with analysis on their preferred labeling terminology, can be explored in this tracker.

‘A direct threat’

The feelings about these products as reflected by the comments ran the gamut. While some were extremely supportive of the innovation cell-based meat represents, some were defensive about the threat the sector may pose to traditional animal agriculture.

Cell-based meat proponents are building an entire industry on the promise of removing the need to raise and kill animals from the food equation, and in doing so, avoid the livestock industry’s inherent environmental and ethical issues. The comments from those defending traditional agriculture are some of the most impassioned.

“Laboratory manufactured proteins from cultured cells is a direct threat to the livelihood and economic well-being of U.S. producers nation-wide,” wrote Agri Beef, a small company of cattle producers. “Manufacturers of cultured cell proteins have a goal to not only replace traditionally raised meats but also demean and disparage the natural production process of traditional meats, while obscuring and withholding their process of production process to consumers.”

The North Dakota Farmers Union, made up of those in that state’s agricultural industry, agrees with that sentiment in its comments.

“Allowing products comprised of or containing cultured animal cells to be labeled ‘meat’ or ‘poultry’ would place family farmers and ranchers at a disadvantage because it will be difficult for them to differentiate their products from cultured animal cell products,” the group’s comments read. “Family farmers and ranchers want fair competition between their slaughtered meat and poultry products and products comprised of or containing cultured animal cells. Fair competition requires truthful and accurate product names and labels for products comprised of or containing cultured animal cells, which will allow consumers to make informed choices about their purchases.”

Cattle near Stoneville, South Dakota.

But not every agriculture industry commenter seemed opposed to the concept of cell-based meat. The American Farm Bureau Federation — an advocacy group which has members from all areas in agriculture — passed a policy that supports limiting common meat terms to products from slaughtered animals in 2019. While the group quoted from this policy resolution in its comments, it also noted that the comments were not an attempt to keep new technologies out of the marketplace.

Several state agricultural departments weighed in on the debate. Absent federal regulations defining cell-based meat and setting guidelines for labeling, many states took matters into their own hands and passed their own laws largely premised on protecting the incumbent meat industry — even though actual products were years away from appearing on menus and in stores. According to the Good Food Institute, 13 states currently have laws on the books dealing with labeling of cell-based meat.

Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner Ryan Quarles, who championed 2019 state legislation that would prohibit cell-based products from being labeled meat in the state, reiterated in his comments why he found the issue so important.

“I believed then, as I do now, that such products should not be allowed to be marketed the same way as products from traditional animal agriculture,” Quarles said. “I believe this issue to fundamentally involve the principle of transparency. Consumers deserve to know that the word ‘meat’ means something, and that it means meat from an animal.”

U.S. Sen. Mike Rounds, a Republican from South Dakota, cited these state laws in his comments. He said that “imprecise labeling regulations” could result in consumers being placed at a disadvantage when making choices in what to eat.

A traditional butcher’s counter.

Permission granted by Tim Fields

Commenters who defended traditional agriculture tended to agree with the policy passed by the American Farm Bureau Federation: Terminology customarily associated with meat from a slaughtered animal should not be used for cell-based equivalents. How far the labeling should diverge varied among the commenters.

The Arizona Department of Agriculture’s Animal Services Division wrote that it understands meat to be skeletal tissue that comes from living and breathing animals — two things that cell-based meat is not. Additionally, many mentioned that terms like “breast,” “loin” and “flank” all refer to parts of animals’ bodies — and should not be used when the meat did not come directly from an animal’s body.

The type of terms to differentiate meat that comes from cells ran the gamut. In its comments, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, which advocates on behalf of the beef industry, referenced research it had done in 2021 about potential terminology and consumer confusion. Names that referenced how the products were made — including “cell-cultured” and “lab-grown” — led to greater consumer understanding of what they were. The group found that “lab-grown meat” was the easiest to understand.

“Allowing products comprised of or containing cultured animal cells to be labeled ‘meat’ or ‘poultry’ would place family farmers and ranchers at a disadvantage because it will be difficult for them to differentiate their products from cultured animal cell products.”

North Dakota Farmers Union

Agriculture group

Other commenters leaned more toward terminology that definitively painted the products as something other than real meat. The Tennessee Farm Bureau Federation endorsed the label “imitation food product derived from meat and poultry,” arguing that cell-based meat is an imitation of what comes from an animal.

The California Department of Food and Agriculture’s Animal Health & Food Safety Services Meat, Poultry and Egg Safety Branch — the regulatory body in the state where many of the most developed cell-based meat companies are located — took another more extreme look at how the products should be labeled.

“Terms such as ‘Artificially Grown Animal Tissues,’ ‘Artificially Produced,’ ‘Manufactured Animal Tissue,’ ‘Man-Made,’ or similar statements that are truthful and factual to the nature or source of the product should be included in the product name.”

Cultivating industry growth through flexibility

For the most part, the comments from cell-based meat companies and their defenders lacked the drama of those that came from traditional agriculture.

But some, like the comments from The Better Meat Co., attempt to show the fight against cell-based meat as an exercise in futility. Better Meat is not in the cell-based meat business, but it produces protein for meat analogs from through fermentation. It likens meat to ice, which was once only obtainable naturally during cold temperatures, but now is available year-round thanks to technology.

“While the ‘natural ice’ industry barons of the 19th century railed against what they derided as ‘artificial ice’ (ice made via new human technology rather than in nature), we all know that the end product is still the same,” Better Meat wrote. “Similarly, some detractors of this new meat industry will argue for prejudicial names designed to turn off consumers. But in the end we must treat this new industry fairly and without protectionism for the incumbents in the sector.”

Aleph Farms’ cell-based steak.

Courtesy of Aleph Farms

The Good Food Institute, an advocacy group for alternative proteins, argued that cell cultivation is a new way of creating products that have existed throughout human history, so new standards of identity are not needed to differentiate cell-based meat. After all, the group wrote, new standards of identity were not required for meat made through cloning. The companies growing meat from cells will want to voluntarily differentiate themselves through labeling, the group wrote.

At this point in time, GFI wrote, regulators should take it slow in creating labeling regimes for cell-based meat products, and instead emphasized the need for flexibility as consumers develop an understanding of cultivated meat.

“Historically, labeling requirements have not created consumer expectations; rather, they have codified existing ones to ensure consumers continue to receive the products they have come to expect,” the group commented. “Consumer expectations regarding cultivated meat and poultry products have not yet solidified and cannot be accurately measured at this time, so there is nothing to codify.”

Upside Foods, a California-based cell-based meat company that recently closed a $400 million funding round that will build its first commercial-scale production plant, also touted a flexible approach to labeling at this time. Creating strict standards right now, the company argued in its comments, could stifle innovation — which could have the unintended consequence of making further developments in the technology more difficult and more costly, both to companies and consumers.

Upside Foods echoed research done by GFI on the basic tenets of what to call these products. A survey conducted by the industry group last fall showed 75% of companies making cell-based meat wanted the products referred to as “cultivated meat.” In its comments, the company also discussed consumer research it had done into labeling terms. Upside Foods found that among consumers, a potential label of “Chicken (cultivated from chicken cells)” represented an accurate association to what the product is. It received a high descriptiveness score, the company said, beating out “cultured meat” and “clean meat” — a term that was once favored by the cell-based meat industry. And it accurately describes that the product is meat, which is important because a person with a meat or seafood intolerance is also likely to be unable to eat these products.

Wildtype’s cell-based salmon sushi.

Courtesy of Wildtype

“By using terminology that is accurate and objective and does not denigrate cultivated or conventional product categories, the approach allows the industry to grow and innovate without disparaging other products,” Upside Foods wrote.

Fork & Goode, a New York-based cultivated meat company concentrating on pork, said that a good labeling parallel in this case is “organic” — a general term that is well recognized, but that is also shorthand for a long and distinct process.

“‘Cultivated’ brings to mind the ancient transition from hunted or gathered sources of food from nature to the adaptation of what has become known as food from ‘agriculture,’” the company wrote in its comments. “Similarly, cultivated meat marks the transition from meat derived from slaughtering domesticated animals to the harnessing of animal biology to grow animal cells for food outside the animal.”

In arguing for the term “cultivated” to be applied to these products, Israel-based cultivated meat company Aleph Farms wrote that they should not have the term “lab” in their names. Cultivated meat is not produced in a laboratory, but instead in food processing facilities. Aleph Farms also argued terms including “imitation,” “mock” and “artificial” have no place on these product labels. They will be grown from actual cells and should have an identical composition to meat from animals, so consumers with meat allergies or sensitivities would also have be allergic or sensitive to cell-based meat products.

“By using terminology that is accurate and objective and does not denigrate cultivated or conventional product categories, the approach allows the industry to grow and innovate without disparaging other products.”

Upside Foods

Cell-based meat company

“[I]t would be misleading — and potentially dangerous — to present cultivated beef as ‘imitation,’ ‘mock,’ or ‘artificial’ beef, as a consumer may incorrectly understand that the product does not contain beef,” the company wrote.

Food companies that have invested in the cell-based meat space used their comments to defend the need for flexibility and accuracy in labeling. Tyson Foods — which has no cultured meat division of its own but has invested in Upside Foods and Future Meat Technologies — wrote it is in favor of fair and honest labeling that is transparent and informative to consumers.

“Tyson Foods is supportive of labels that use the appropriate qualifier, e.g., ‘cultivated, cultured, or cell-based’ along with the appropriate standard of identity or common or usual name,” the company wrote. “In order to provide a path forward for consistent labeling, Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) should ensure product names are recognizable and understandable to consumers, inform consumers that some or all of the product comprises cultured animal cells, and are not ultimately misleading and confusing when compared with the names of traditional products on the market.”

Other comments

A variety of groups, some advocacy and some academic, attempted to advance their agendas through their comments.

One of the platform issues for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals urges consumers to adopt a vegan diet and end industrial-scale farming. At the moment, it’s unclear whether vegetarians and vegans will accept cell-cultured meat as something they can eat, but PETA’s comments try to further its viewpoint in terms of animal-based product labeling. The group gives its suggestions for labeling of cell-based meat, but what it really wants is specific labeling on traditionally farmed products.

“The most straightforward approach to ensure that consumers are able to make informed choices is to always disclose the presence of ‘slaughtered meat’ in food products,” the group’s comments state. “This language is clear, concise and does not rely on understanding of animal cell culture technology.”

Other consumer groups used this as an opportunity to call out broader concerns around food tech.

A bioreactor for Eat Just under construction.

Courtesy of Eat Just

The Center for Food Safety, a group aligned against the negative impacts of industrial agriculture — but most specifically GMOs and industrial chemicals — entered two comments on the docket. One was a petition signed by 6,028 members that called out companies that “are attempting to grow cells from meat and poultry in huge vats” and opposed USDA allowing production or labeling of cells using fetal bovine serum as a growth medium. The petition also asks USDA to ban any product using genetically engineered cells that signatories say causes cancer, and asks that any company using genetically engineered cells signify it on the label.

In its official organization comments, which were submitted in conjunction with Food & Water Watch, Center for Food Safety reiterates and explains these concerns with growth medium derived from animals — which most companies in the space are moving away from — and genetic engineering processes. But the group also drives home how unnatural it believes the process is.

“‘Synthetic cell-cultured meat and poultry product’ could be the generic product name, with the product specifying which animal cells it derives from,” the comments from both groups read. “For example, “‘ with synthetic cell-cultured protein derived from bovine cells.’ ‘Synthetic Cell-cultured’ would not risk confusion with other cultured products.”

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, a trade group for those in the nutritional field, submitted comments from its standpoint of working with consumers through food labels. The group urged USDA not to call these products simply “cultured,” since that term has a different meaning to consumers and applying it to cell-based meat isn’t quite analogous. Buttermilk is a type of cultured milk, which is created through bacterial cultures modifying the milk itself; it does not create a new product, the group wrote, In the case of this type of meat, the culturing process actually does create the product.

Several groups and departments affiliated with the government and industries in Canada entered comments as well. While Canada would write its own labeling regulations for this segment, many of these comments were aimed at asking the United States to write regulations that would be a closer fit with those currently on the books there.

“Though the topics covered within our consumer research vary, one consistent thread is that consumers value transparency when making food choices. In alignment with this theme, IFIC supports efforts by FSIS to increase consumer clarity on meat and poultry products made with cultured animal cells.”

International Food Information Council

Science-based food research group

Groups representing other animal-derived food products also weighed in as part of the comments. The United Egg Association, the American Dairy Coalition and the National Milk Producers Federation, as well as other agricultural groups, all asked that similar federal labeling regulations be instituted for companies that are making egg and dairy proteins that do not come from animals.

Many food-industry-affiliated groups left comments urging lawmakers to be deliberative.

The International Food Information Council, which focuses on bringing food and health science to consumer research, pointed to findings from 2020 consumer research about cell-based meat. It found almost one in five consumers would buy a cell-based product after the concept was explained, while 74% would opt for the traditional animal product.

“Though the topics covered within our consumer research vary, one consistent thread is that consumers value transparency when making food choices,” the comments state. “In alignment with this theme, IFIC supports efforts by FSIS to increase consumer clarity on meat and poultry products made with cultured animal cells.”

What next?

Now that these comments are being evaluated, Kulkarni said that USDA and FDA will work together to decide on labeling terms. A spokesperson from USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, which handles cultivated meat regulation, said they do not have a timeframe on when their work will be completed, but there are no plans for additional public meetings.

USDA has indicated that it will not necessarily wait for these rules to come out in order to approve products for sale, Kulkarni said. Wholesale determinations that products are safe for consumption may come first. If that is the case, FSIS will approve each product label individually with the ongoing rulemaking process in mind. The USDA FSIS spokesperson said that they would ensure all labels approved before this rule is finalized are not false or misleading. Additionally, any companies with products going out on the market will be told that labeling requirements could change as the process completes.

A cell-based hamburger made by Mosa Meat.

Courtesy of Mosa Meat

“Those product-specific determinations will inform the labeling process and so that’s something that I think is worth observing in the near future,” Kulkarni said. “If FSIS agrees with certain labeling terms or the presentation of certain labeling, that’s an indication that that kind of labeling should meet the future rulemaking that the agency ultimately finalizes — or at least those determinations should shape and inform that rulemaking.”

FDA and USDA’s FSIS have also agreed to establish joint principles for labeling and claims. This means that although the agencies don’t jointly regulate all of the products to use cell-based production — FDA solely regulates most seafood, for example — they will work together to establish a consistent labeling framework for all products.

“That’s just good policy because these products are going to be jointly regulated by FDA and FSIS,” she said. “There should be a mechanism to assure consistency in labeling determinations.”

Right now, the comments are being reviewed by many people working with FDA and USDA, Kulkarni said. Departmental staff is looking at them, including technical teams of scientists and policy teams who are experts in food labeling, laws and regulations. Lawyers are also likely looking at the comments to see if there are any First Amendment issues. Kulkarni said it is important that labeling laws don’t restrict commercial speech and that they work under existing case law governing federal food labeling.

In general, Kulkarni said, FDA and USDA are guided by the requirement of giving food a truthful and descriptive designation. This takes into consideration the food’s basic nature and essential characteristics, which include its source and characterizing features. All of these aspects are brand new and need to be defined for cultivated meat and seafood.

One of the things Kulkarni is watching for is how specific FSIS applies some of the definitions and terminology for cell-based meat and products. The questions in the advance notice of proposed rulemaking ask some pretty specific things about cultured meat products, including whether standards of identity involving this kind of meat should be established, what the differences between slaughtered meat products and cell-based ones would be, potential label claims on cell-based meat products and whether products made with cultured meat as ingredients would need to be specifically labeled as such.

Kulkarni said that in looking through the comments, federal regulators will categorize them by the types of groups or individuals who made them. This can help signify how different groups of people — be they farmers, meat processors or scientists — feel about the space, and determine where there is consensus.

“Meat is a very big part of American culture, and so there’s a lot of people really interested and passionate about these issues. At the same time, the world’s population is growing, and we understand more and more of the potential impacts of climate change. So a good number of people are reevaluating how and what they eat.“

Deepti Kulkarni

Partner, Sidley Austin LLP

While it feels like it’s been a long time since this process started — there was an initial public meeting in July 2018, which kicked off the discussion of regulation and labeling between FDA and USDA — Kulkarni said from a regulatory standpoint, it’s moving quickly. The joint regulatory agreement came in 2019, and the agencies have been working with companies in the space since then.

Considering the work that has been happening on both sides, Kulkarni said it is not outside the realm of possibility that there will be decisions issued regarding some of these companies’ consultations with regulators this fall. And while Kulkarni is not privy to what kinds of decisions may come out first, she said they would be likely to do with safety, meaning that the products would be deemed suitable for human consumption.

When reviewing a few of the comments herself, Kulkarni saw a lot of differences of opinions. But she saw one thing that most commenters agreed on: Cell-based meat should be labeled in a way that differentiates it from products that come from slaughtered animals.

“That is a bit of an evolution, I think, from where this debate initially started,” Kulkarni said. “Initially, the debate felt very black or white, right? One way or no way. And now we’re seeing some of the nuance bear out.”